Marilyn Kilmister is entertained by the sight of his own blood. He’s been thrown through tables, off balconies, had his body stapled, thrashed with barbed-wire, smashed by light tubes, lemon-juice poured into the cuts. He says he was afraid of being set on fire until he did it.

“Who trained you?” he screams. “Who fucking trained you?”

He knows who trained me.

“Trevor and CJ.”

“Trevor and CJ are your friends. I’m not your friend. I fucking hate you. Get out of the ring.”

I get out of the ring.

Marilyn calls me back in for a guy named Jamal to work a heat on me. His job is to look dominant, own the ring while he beats me up. My job is to react as if his strikes are real, to gain sympathy from an imaginary audience. The heat is the equivalent of the ‘deathtrap’ in film. The scene where Goldfinger has Bond shackled, torturing him by laser. But through a fatal flaw on the villain’s part and (or) deus ex machina, the hero escapes and overcomes his foe. With Jamal dominant, he g-walks around monologuing to the gym walls. In a match situation this would be where I make my comeback but Marilyn yells, “Stop!”

We’re motionless while he addresses Jamal, “Your movement is awful. You look like a fucking robot.”

Jamal takes it with a sad dignity because the thing about Marilyn is he’s always right.

“You,” Marilyn says to me. “Work a heat.”

I work the most generic sort of heat, circling and stomping. I let out a guttural roar while glancing Jamal harmlessly with the sole of my foot, giving the impression that I’ve kicked him, while my other foot stomps down on the ring. It squeaks and quivers like an old truck. Jamal wails and rolls to another part of the canvas. In the world of staged violence, everything needs to be big. The sell needs to be big. Every non-strike has to be exaggerated and amplified deep into the crowd. The trick with a heat is to do as little as possible. Too many strikes give the game away. As the bad guy, or heel, you need to do just enough for the good guy, or babyface, to sell your abuse and for the crowd to feel sympathy for them while you make a spectacle of their suffering. I quickly think of the next move I want to do, grab him round the neck and throw him over vertically onto his back.

“Stop!” Marilyn yells. “Why did you do that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why don’t you know?”

“I just… did it.”

“The more moves you do the less they mean,” he says. “Who’s he, fucking Superman?”

“No.”

“Well he must be if he can kick out of all of this,” he flicks the tail of his undercut. “Either that, or your moves are shit.”

* * *

I knew it would be tough but I never expected this. In training, there’s nowhere to hide. No crowds or costumes. Stripped of the theatre, it’s just two guys play-fighting in a room while another guy screams at them. Pro wrestling isn’t a genuine “sport”, it’s a form of drag where men dress up as men. The matches are choreographed and the outcomes are predetermined. In the past, to protect the integrity of the industry, nobody admitted that it was fake. Wrestlers lived under a strict code of honour known as kayfabe that dare not be broken.

Kayfabe is a pact between audience and performer, a suspension of disbelief. It is the idea that if we present events and characters as real and you pretend you believe in the truth of them, you’ll feel genuine emotion.

I stand in the ring, rubbing my elbow. My knees burn. Something unknown in my back aches. The wind has been bashed out of my body. The first thing you realise when you get in the ring is the physicality of it. How much it hurts. Watching wrestling on TV doesn’t give a sense of what it feels like every time you hit the turnbuckle pads or have another person land on you. The ring is made from judo mats covered by a canvas above boards, slatted over metal beams. A fall doesn’t hurt the way wrestlers make it look. But it’s still violence on the body. Doctors have equated that every bump is equal to a 20mph car crash.

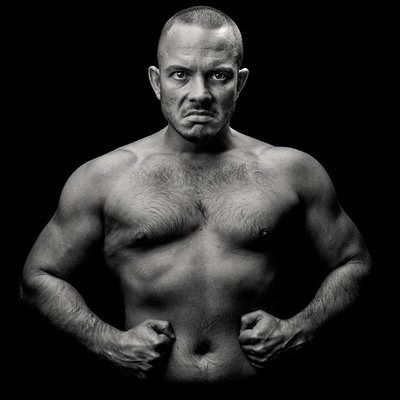

Marilyn says we have five minutes to plan a match. Jamal is a European powerlifting champion. He’s six-foot-tall and fourteen stone. This would be small by WWE standards but he’s on the larger side for British wrestling. A bit bigger than me. His character is that he’s a powerlifter and calls himself ‘Jay Langston’. He wears his medals to the ring. His entrance music is Power by Kanye West.

Now’s he’s the babyface and I’m the heel, acting all cowardly and sheepish about facing him. Nobody likes a chicken-shit but I always dreamed of being a heel. The role seems like a vessel to pour all of my aggression and frustration into. I want to be hated. It’s the family business after all. Long before I was born, in the wild west of the seventies, my dad was touring the world as a pro wrestler, using the name Earl Black. He worked across North America, the Far East and Australia. My youth was filled with tales of road trips, wild fights, tough guys who lived lives like action heroes. He worked as a heel and back then, when people believed sincerely in kayfabe, he would often run for cover after his matches. I want to be a heel like my dad. So, when he tries to lock-up, I back off. He tries to lock up again and I poke my body through the ropes, squirming out of bounds. When we finally lock-up, collar-and-elbow, he heaves me off and I take a back bump, shaking my head in disgust.

“Stop,” Marilyn says. “Both of you, stop. What am I going to say?”

“I don’t know,” I answer.

“Why are you bumping around for him like that?”

“Because he’s a powerlifter.”

“Yeah, but he’s not Andre the fucking Giant, is he? Look at him. You’re roughly the same size. He might be stronger than you but it wouldn’t be obvious on a show and you wouldn’t fall about like that would you?”

Marilyn talks us through the choreography of a headlock sequence.

He calls it to us step-by-step.

We lock-up and Jamal powers me into the corner to demonstrate his strength. The same thing happens again. The third time, he backs away sportingly and releases his grip. But I snatch a headlock and won’t let go.

There’s a lot more to the sequence that I still can’t remember. We get every step wrong. Marilyn screams at us and we start again. This happens about thirty times.

I feel like I’m melting but also take a perverted joy in the abuse. It will make a good story. Marilyn screams at us for nearly three hours. Until eventually we run out of time.

We sit down before we get changed and Marilyn asks, “What is wrestling?”

“It’s a spectacle,” I say thinking of Roland Barthes. Trying to be clever. Hoping it will make him back off.

“It’s sports entertainment,” Jamal says.

“What does that fucking mean?” Marilyn asks.

We don’t know.

“Wrestling is storytelling” he says. “We tell stories.”

The stories are simple, enacted through gesture, like dance, the story of two bodies, moving. I’ve been training as a pro wrestler for a few months. I signed up to an intensive course to be match-ready as quickly as possible.

Sometimes I’m the teenage boy who dreamed of lacing up his boots and getting in the ring. I would wrestle my brother in my bedroom whenever my Mother went out. I’d take bumps on bare floorboards. Told him to hit me with a chair and then made myself bleed by dragging a pencil-sharpener blade across my forehead. But my fantasy didn’t include someone like Marilyn.

“Why do you wrestle?” he asks.

“To win,” Jamal says.

“And what does your character get if you win?”

I’m silent.

“He gets paid more,” Marilyn says. “At its most basic level, that’s your motivation. Every wrestler wants to get paid. You get the winner’s purse.”

We nod.

The winner’s purse is a kayfabe idea. Wrestlers don’t actually get more money for winning than losing. They have an agreed rate like any freelancer.

Marilyn asks me, “Who’s your character? Why does he wrestle?”

“Dirk Dresden.”

“Who the fuck is Dirk fucking Dresden?”

“He’s a Judge Dredd style guy, maybe from the near future.”

“The near future?”

“Yeah.”

He replies, high-pitched in disbelief, “How the fuck can he be from the future?”

“I don’t know.”

“If he was from the future, why the fuck would he wrestle?”

“No idea.”

“You’re supposed to be intelligent, a fucking writer, and you’re telling me you’re going to be a law enforcement official from the fucking future?”

Part of me has already left my body and is on the tube home. But I’m still here, having my sense of self punished by rhetorical questions. I can take the bumps. The blows. The physical abuse. It’s the questions that hurt. The feeling that somebody can bear witness to your inner fears, identify your insecurities, become intimate with them and then take great pleasure in tearing you apart. I tell myself I don’t want to be a wrestler. I’m only doing it because this is the last card I have to play at being a writer. My first novel was rushed to publication. For my second, I lost my book deal because I couldn’t finish it. Fiction just felt too fake to me. Even then, there was still something authentic I craved from writing and wrestling was a part of me that I had laid dormant. I wanted to fulfil a juvenile ambition and it seemed a gonzo way for me to write something interesting. But my dad would never have written about this. He’d never have broken kayfabe. Long after the truth of the business was revealed, he was still pretending otherwise. I grew up believing these stories were real. Looking through his scrapbooks, old sepia photos of cartoon masculinity, the myths were as fabulous and artificial as the fiction I was writing. As kayfabe as the idea that I was a writer with anything to say. I knew it was a fiction and the people humouring me knew it was a fiction. Yet we persisted. The trouble is, knowing something isn’t true doesn’t stop you believing.

“Why do you wrestle?” Marilyn demands in his Dartford scream, “Not your fucking character. You.”

I take a deep breath. I want this to end. But I need to go where he’s leading me.

“Because my dad was a wrestler.”

“What was he called?”

“Earl Black.”

“There you go,” he says. “You’re Earl Black Jr.”

Wes Brown is a pro wrestler and PhD student researching masculine performativity and creative nonfiction at the University of Kent. His work has been published in Litro, Aesthetica, Poetcasting, The Cadaverine and Culture Wars. He tweets as: @wesbrownwriter