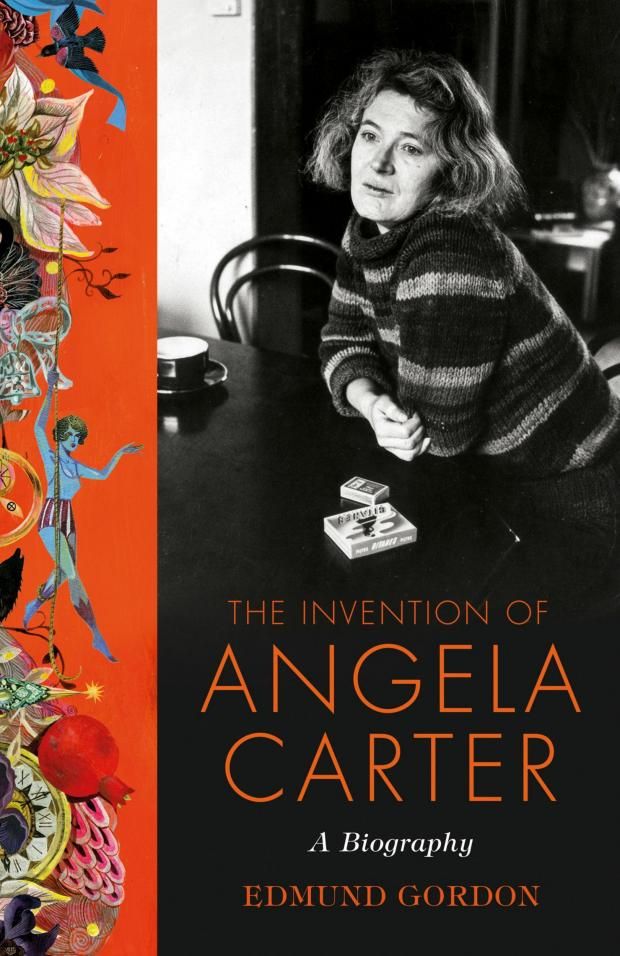

Angela Carter is as much a work of fiction now as any of her novels; to use her name is to summon an image we create together. It is more than two decades since she passed away and in that intervening space the myth of Carter has grown, she has become unpindownable – a collection of allusions, anecdotes, an identity divorced from any physical agent who might shape it with their life. Of course this is true of anyone we talk about in their absence. In Edmund Gordon’s The Invention of Angela Carter, we spend time in the company of the absence of Angela Carter.

Carter’s absence extends into her life. Gordon’s introduction begins on a television interview Carter gave one month before her death of lung cancer at fifty-one, for the BBC’s arts series, Omnibus. He describes Carter’s active involvement in the production, ‘making requests and offering suggestions about almost every aspect’. This final, potent moment of self-portraiture in Carter’s life allows Gordon to pose his thesis for the following four hundred-odd pages; ‘the story of [Carter’s] life is the story of how she invented herself’. Gordon’s portrait of Angela Carter is of a woman who seems to prefigure her own later absence, building the myth of herself throughout her own life.

Gordon soon dispenses with ‘truth’ and verity. In researching Carter’s life, he writes, ‘her closest friends… have told me things that can’t be true.’ An ‘appreciation’ published in the Guardian two days after her death received an indignant response letter from a close friend, when it described an encounter with her smoking on a bench in Clapham ten years after she had quit. Almost immediately after her death, Carter is subsumed into conflicting accounts and efforts to define the woman she was. Gordon accepts this wholly. From the off he is telling us a story, with its own limitations on veracity.

Carter emerges in tension between her own diaries and letters and others’ accounts of her, a sort of semi-folk figure that in neither aspect entirely inhabits fact. Gordon’s portrayal of her has a casual attitude to the places where the testimonies run thin; he writes, ‘I’ve tended to rely on [Carter’s] account when I haven’t encountered anything that obviously undermines it.’ This is Carter’s story, of which Gordon casts himself as facilitator. The text is full of episodes in her life which can only be taken from Carter’s own account. When leaving Japan, after deciding to divorce her then-husband, Paul, ‘at the airport she cried… then, in a final, private gesture of extravagant symbolism, she took off her wedding ring and left it in an ashtray in the departure lounge.’ What adds to this moment of drama is the knowledge that it only comes to us in the retelling. At some point in her life, Angela Carter made the decision, either to make this action, or have people believe she did. Either way, this is Carter’s story, we have only her to go by.

Gordon expresses disdain for depictions of Carter as a harmless, benevolent grandmother-figure. The Angela Carter he shows us is capable of a sparkling, natural cruelty as much as she is of warmth. A trap acquaintances of Carter make frequently is believing her to be all benevolent softness. She is an exerciser of benevolent cruelty in equal (or greater) measure. Gordon is keen to portray Carter as a woman who wasn’t necessarily kind and wise but lived life as it came. Her life was various and surprising, yes, but the lion’s share of the surprises were for her first.

My experience of reading The Invention of Angela Carter has become peculiarly devotional. I approached the reading of it as someone invested in her prose, novels, and I put it down invested emotionally in the idea of her. We invent the people we choose to care about, including ourselves. I have opted in, now, to contributing to the communal, spectral idea of Carter that outlives her. Whether they’re famous authors or not, there is a creative element to every story we tell about a loved one, or ourselves. They are all acts (even if unwittingly) of self-portraiture. In telling, we reveal our own lens.

Some of the voices Gordon ventriloquises did not live to see the book completed. There is a sense Gordon himself is among those ghosts, only partly able to contribute to the shaping, and some of the details, of this telling of the life of Angela Carter. The real achievement of Gordon’s in The Invention of Angela Carter is the persistent sense that he is not in the driving seat of this story. That privilege is given to Carter, who though she may be twenty-six years dead, just needed a bit of a hand with the engine.

James Varney is a writer and theatre maker based in Manchester. He has had work presented at Derby Theatre, the Royal Exchange Theatre, and Camden People’s Theatre. He tweets @mrjvarney and maintains a blog of cultural criticism at www.jamesvarney.uk