Whenever I imagine my father, he’s almost naked.

For three years after my parents divorced, I spent every weekend with him. As soon as he had settled in for the evening, he would strip down to old white briefs and walk around his rented apartment. I knew there was something sordid in the act, but to this day, I would attest to a queer kind of innocence in him.

I recognized predation by then. I’d had a babysitter who masked touching as tickling. When he shoved his fingers up inside me, I thought of the stained-glass window boarded up inside our house. You could see from the yard that its gorgeous colors, blocked by the horrid 60s paneling that served as our living room wall, strained to stream forth. I tucked the truth of what happened behind that window and knew the light would never shine through.

My father was different. He was lost, bedevilled by OCD. He opened and shut the refrigerator dozens of times as if seeking his soul inside.

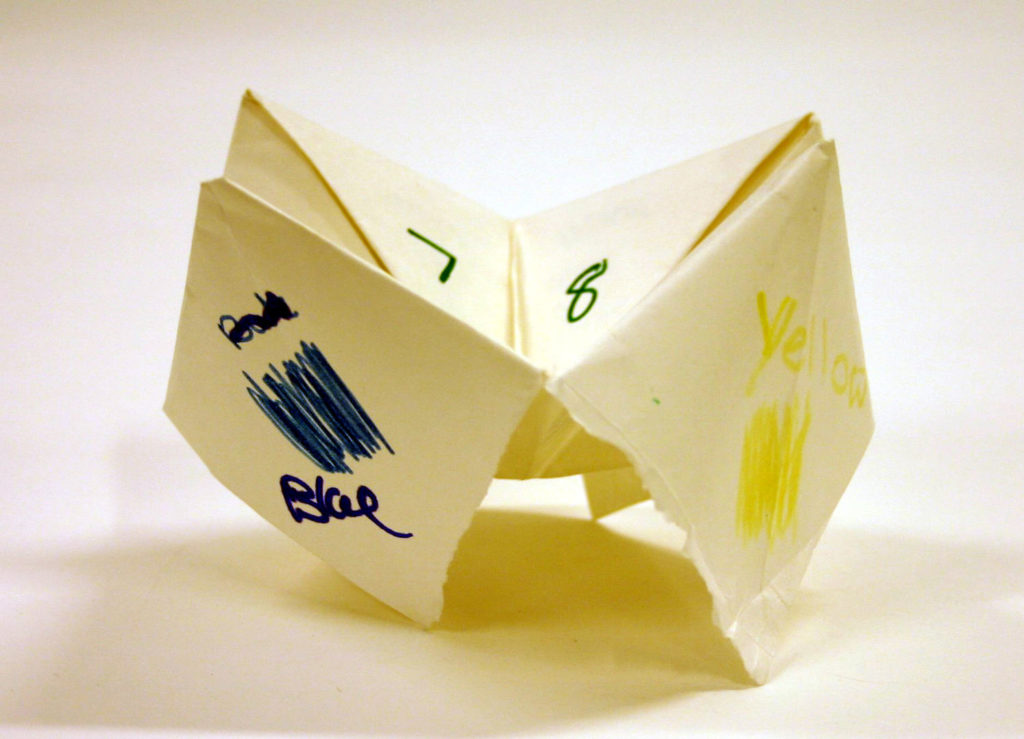

And he had a broken heart. Even at age seven, I could see that he was still besotted with my mother. She had insisted on the divorce. One day, he and my brother and I were driving to visit my grandmother in the Berkshires. While my brother was at the wheel, I showed my father the fortune teller paper game I’d learned at school, in which an origami flower flicks through your fate. You had to fold the paper just so and write out information on each petal. In this case, I was trying to divine who my father might marry the next time. I needed names. The first he chose was my mother’s. That’s flimsy evidence, but I also couldn’t help but note his continued curiosity about her life.

My father was renting a two-story apartment at the edge of historic Lexington, where he taught math at the local high school. Like my mother, who lectured in physics at Suffolk University on Beacon Hill to put herself through her final years of graduate school, he had gifts as a teacher. Years later, a friend of mine who’d done a stint as a teaching assistant at Lexington High as part of her M.Ed. confirmed that the students spoke well of him. I don’t doubt it. A rapport with students seems to run in my family; however troubled we are, we use it to connect with young people seeking answers.

“I tell it to them straight,” he said to me more than once. “And I tell them about my daughter, who’s so smart and takes everything so hard.” I believe that he cared about his students. I imagine he saw helping them as a vicarious way of saving me.

**

Every Friday night from age seven until just after I turned ten, my father would pick me up in Melrose at my house with the boarded-up stained glass window and the lilac trio. We’d usually stop at McDonalds on the way to his place. I always ordered French fries, nothing else. Sometimes we’d swing by Toys R Us to buy me a Strawberry Shortcakes miniature doll or Charmkins trinket. I loved anything tiny, fragrant, and crowned with a delicious name. Lime Chiffon, the green-haired, stripe-socked ballerina of the Strawberry Shortcakes universe, delighted me with her tutu and leg extensions. Among the Charmkins family, I most treasured, due to her sobriquet, Hyacinthia, a one-inch-tall African-American girl clutching hyacinths who could be attached to a ponytail holder. Both smelled like waltzing flowers magicked from a world of sweets.

Sometimes, though, I told my father that we didn’t need to stop at Toys R Us. I felt a vague guilt—or better to say, I felt his guilt and how he sought to appease me. It was painful to inhale adults’ moods. The scents of my miniature dolls were so much more untroubled.

My brother was seven years older than me. Fourteen when our parents divorced, he had elected to live with my father, but he spent much of the weekends elsewhere.

One night when I was eight, I was watching television and reading in the downstairs living room, where I slept on the couch. My father’s apartment was in an old building and consisted of a hive of small rooms. One or two could have been converted into an extra bedroom if my brother hadn’t stuffed a pair of them with old boxes, newspapers, racing-track programs, fireworks, unopened mail, and other trinkets.

I was lying on my stomach and flipping through my book when my father entered, wearing nothing but his sagging, threadbare white underwear, as always. He reached down and touched the cleft between my buttocks.

“I’m touching you in the rear,” he said, in the voice of a demented child.

It was less my experience with my babysitter than a recent talk with my mother that compelled me to put him in his place. My mom had sat me down for one of Those Talks, which were always accompanied by a set, terrified expression on her face. This one was about how I should never let adults touch me. As a child, I avoided confrontation as much as new foods. So what I said next was likely factored by my desire to follow the good-girl script my mother had recently charged me with:

“You’re not supposed to touch me down there.”

I will tell you what I saw then and see now in memory: He looked wounded.

I felt responsible for rejecting him.

I still do.

“It’s your mother, isn’t it? She’s trying to teach you to be afraid of me.” He left the room. I continued reading. Whenever adults do something inexplicable, keep reading. Pretend not to notice—that had been my motto for years already.

I still wonder what he would have done next if I hadn’t stopped him. I’m not sure he knew.

**

At Amherst College, I started studying Japanese literature. In graduate school, my specialty was the modern period, slim volumes of rarefied transgressions by writers like Tanizaki, Kawabata, Mishima, and Kafū. But in college, I fell hard for the thousand-year-old Tale of Genji, which is a very thick volume of rarefied transgressions. Arguably the world’s first novel and first psychological novel, The Tale of Genji was inked by a woman of the Heian court and chronicles the romantic adventures of an idealized prince in the ancient capital of Kyoto.

What struck me on a recent rereading was how prominent incest is in the story. Its main theme is the impermanence of life and the feeble comforts of beauty and desire, so it’s no wonder that whenever Genji loses a woman he loves, he replaces her in his heart and bed with someone else. These substitutions skirt incest again and again. Genji’s mother dies when he’s a child, so his father, the emperor, replaces her with a nearly identical beauty the text identifies as Fujitsubo. Not surprisingly, Genji transfers his affection to his stepmother, and when he becomes a teenager, their relationship veers sexual. In time, he swaps out Fujitsubo, who puts an end to their affair and eventually becomes a nun, for her niece, a lovely child called Murasaki. Many years later, he lusts after a young woman he shelters in his compound; while he knows she is no blood relation, everyone else believes her to be his daughter.

In a world where breeding with the emperor was the goal of many families and men and women were segregated throughout most of their lives, such fraught tensions between actual or surrogate kin make a kind of sense. But my failed romance with my father is not an imperial tale from long ago, although I now suspect I was a proposed substitute for my mother. Or perhaps it’s just that I can’t understand any of this any other way. Literary narratives revel in the contradictions that drive us mad in life.

**

My father never tried to touch me like that again, and I never told anyone about it. The weekend visits continued. Less than two years later, though, my mother announced that she and I would be moving to Florida. She had finished her dissertation and received her Ph.D. from Tufts, and she’d always dreamed of living some place warm.

My mother sat me down, the usual strained look on her handsome face. “Your father thinks I’m trying to take you away from him.”

I didn’t know what to say. They had shared custody, but my father didn’t fight for me. We moved to Florida that August. I started fifth grade a week after we arrived.

**

I didn’t see my father again until Christmas. I can’t recall exactly when I started dieting, but I wouldn’t have lost a noticeable amount of weight by the holidays. By the time I flew up to Massachusetts to spend a few weeks with him in June, however, my body was dabbling in German Expressionism.

When I was admitted to my first hospital for treatment of anorexia a few weeks later, my mother informed the intake nurse, “Her weight loss during her visit to her father was dramatic.” I must have mentioned this to him because I remember his protest. The truth, or at least the scale, was on his side. He was so alarmed by my appearance that as soon as he saw me he had me weigh myself. According to his scale, I amounted to 71 pounds; at intake, to 65. Even allowing for some discrepancy in scales or clothing, it does seem true that I lost the bulk of the weight prior to my New England visit. By then, too, I was reveling in my new body and regimen. My maternal grandmother told a friend of hers that I ate “like a bird,” and I beamed at what I took to be a compliment.

When I was committed to my second hospital in the spring of the following year, I called my father and begged him to get me out. I was terrified in that cuckoo’s nest, with its screaming teenagers going through drug withdrawal and restrained patients spread-eagled on their beds like torture victims on a medieval rack. He drove down from Massachusetts—he fears flying—and talked to my doctors. He didn’t succeed in extricating me. At one point, he asked my chief psychiatrist when I’d be released, and the latter responded, “Well, her insurance runs out on X date.”

After I was released, a few weeks before that insurance deadline, my father confessed that he thought I’d used him. From this distance, I can’t say if his feelings were justified. I may have called him less after his aborted attempt to rescue me, but I don’t think he understood the exigencies of the psych ward. As soon as you are incarcerated in one, your full focus turns toward when you can leave it; unlike criminals, certifiable patients don’t have end-dates on their sentences when they enter. Today, all I can say for sure is that he was complaining like a spurned lover.

**

I may have rejected him first, but my father got in the last word. During my senior year of high school, my relationship with my stepfather deteriorated, so I called my father and asked to live with him. By then, he had remarried (not coincidentally, I think, just after my mother found a new husband), and his sick elderly mother had moved in with him as well. He said he didn’t have the room, which was true.

Still, I interpreted it as my father prioritizing other people in his life over me. Baiting him, I asked, “What more could you want from a daughter?” Translation: What do I have to do for your love?

If I look at it now, this wasn’t such an unreasonable question. I was an excellent student on the verge of getting accepted to Amherst College. That year, I won various school- and county-wide writing awards and scholarships and was a National Merit Finalist. I edited the school literary magazine and was active in drama club and community theater. I never got into trouble at school and had amiable, high-achieving friends. I volunteered walking dogs at the local animal shelter. After an awkward early adolescence, I was finally growing into my looks, although I didn’t realize this at the time. In photos I am tall, thin, pretty.

Yet my mental health history superseded everything. And I knew it. Not long before, I’d called my guidance counselor yelling that I would kill myself because my stepfather had shoved me. Panicked, she contacted the police, who showed up at my house and asked me what happened. When it was my stepfather’s turn, he Tasered my accusation with nine words: “She was recently in a mental institution, you know.” Knowing all this, these words to my father were a form of self-harm, as much as shallow cuts on the wrist. He reacted in kind:

“If you think that . . . Maybe you do need to be on some kind of medication.”

**

As I found stability and a surrogate family in my second marriage, I distanced myself from my father. He’s in the final stages of dementia now, I hear, so he must have forgotten all he could never remember. I feel sorry for him. His memories like the half-kidding furniture of a room at dawn. Paranoia blocking its windows like that awful 60s paneling of my childhood home.

He’d call me crazy for it, but I’d love him if I could

Cynthia Gralla is the author of The Floating World, a novel published by Ballantine, and The Demimonde in Japanese Literature, an academic monograph from Cambria Press. I have also written for Salon, The Mississippi Review, Electric Literature, Entropy, The Ekphrastic Review, October Hill Magazine and B O D Y.