‘My baby humps is sore.’

My three year old is dressed in a diaper and a pair of pyjama shorts, nothing else, and she’s running her index fingers inwards along her ribs. In the last three months, she’s become rangy, long, and her pot belly has melted silkily away to reveal a bumpy line of ‘baby humps’.

‘Your ribs?’ says my husband, taking stock of his place in In The Night Kitchen, leaving naked Mickey, with his little paunch, baby humpless chest and tiny penis to fall alone through the sky into the dough below.

‘Yes, Daddy,’ she says, and if she knew the word, I’m sure she’d utter ‘you moron’ afterwards. Lockdown has escalated disdain for her father to levels I hadn’t anticipated until adolescence. ‘My wibs.’

‘Does it hurt when I do this?’ he asks, stroking a rib with a ginger finger.

‘No, Daddy,’ she says, swatting him. ‘It is not a right time to do this.’

Once she’s in bed, we sit beside each other on the couch and Google, pinging messages backwards and forwards when we find an article that correlates. How to Help your Constipated Toddler Go pops up in a banner across the top of my screen. Neuroblastoma: the facts scrolls over his.

‘She does not have a… a ‘rare type of cancer’, honey,’ he says, exasperated. ‘She is on an egg-only diet. She needs a poo.’

*

When we started to wean her, we gave her everything we ate. Malaysian curry, russet in colour, with blood red flecks of chilli oil sitting on the surface of the chicken and a puffed pillow of roti to dip. Noodle soup with bright loops of scallion that would end up barnacled to her soft dumpling cheeks. Puttanesca scattered with caper pearls so sour her eyes went wide and round. ‘Look at that baby,’ other parents would say, pointing her out reproachfully to their older children in restaurants as she crammed fistfuls of bitter, wizened olives into her sweet mouth. ‘So adventurous.’

She had always been adventurous; flinging herself into the swimming pool, demanding to go on the bungee trampoline at the mall, petting huge, wolfy dogs at the park. But I was proudest of her eating. As a child, I was a fussy eater, on a pizza/plain pasta rotation for most of my life, and it wasn’t until I met my husband (who rightly diagnosed it as learned behaviour, once he’d eaten with my parents a couple of times) that I snapped out of it. He ran London’s first New Hawaiian restaurant, and I tested the menu before they opened, closing my eyes to taste sambal-crusted cod and poké-stuffed avocado and Spam fries with yuzu mayonnaise. I was cured, and determined that when I had this person’s children, they would inherit his tastebuds. And when she arrived, with her love of all things umami, it seemed she had. Until quarantine.

*

Sometimes it seemed to be happening slowly. She was no longer allowed to attend nursery. She’d still speak animatedly about her friends, holding up the animals from her toy ark and naming them after her favourite classmates. Millie, the lion. Connor, the goose.

We’d plate up parmesan risotto topped with Roy Finamore’s broccoli confit and she’d edge a spoon around the plump grains of rice, careful not to touch the heavenly, anchovy-scented green up top.

‘It’s broccoli,’ I’d say, and she would shut her eyes as though she hoped that when she opened them, I’d be gone. I’d plough on. ‘Your favourite. You love broccoli.’

‘No, Mummy. I do not love broccoli.’

Other times, it seemed sudden and violent. My best friend died. In the week leading up to it, when I couldn’t see her, couldn’t go to her, only knew, as did all her other friends, that this was the end, I walked the house cold and bitter, unable to eat a thing. I felt the relief that sometimes accompanies grief when I took the call; the tightness in my chest expanded, I knew the heavy weight of wait was over.

I cooked shrimp and pineapple tacos, flame grilling the tortillas on the gas ring. My daughter looked at the syrupy soy and sriracha coating on the sheet pan and began to scream. I filled her a wrap, sprinkling coriander and yogurt over the top. She flung it at the wall.

*

Five months of quarantine, and now all she eats is eggs. A million of these traumas – big ones, little ones, middling, everyday ones – led us here. Because… what do all of these things mean to a three-year-old?

Her brain doesn’t compute never seeing Laura again; she still expects to pull up outside her house and sit in her garden to eat ripe, golden plums together, juice trickling, wasps murmuring overhead. She asks me, ‘what’s Laura doing now?’ and I say, ‘Laura isn’t doing anything now,’ and she pauses, then presses me. ‘She just doing dead stuff?’

She watches videos of herself as a baby, toddling around the hospital bed while Laura plays peekaboo with her, and she laughs along with her videoed self, because it’s funny, because Laura was funny. When I watch the video my heart catches at the sound of a voice I’ll never hear say anything new again. She must feel it somehow, because then my daughter cocks her head to one side, like she’s seen grown-ups do, and elongates her vowels to create a sympathetic timbre, part of an exaggerated, accidentally comical mimicry of grief that she’s developed over the last few months. ‘Laura dieeeeed,’ she says, shrugging her shoulders.

And even though it’s impossible to understand any of it, in a way, the loss of a person – the missing of her, the absence of her, the gaping, open wound at the centre of our lives – is more understandable than the unquantifiable loss that comes from missing out on weeks and months of moments with her peers. Vital, formative experiences, of playing, sharing, snatching, giving, pushing, falling, crying, soothing, learning, loving, have been taken away, and none of us know what effect that might have on our children’s development. But I’ve been watching her, my proudest thing, and I can see a little.

When we spot other children in the park, she’s suddenly frozen, her breathing shallow. She can’t remember what it is to interact with another kid; it’s become something that happened once, but long ago, an alien, crystallised thought. She goes completely still, her arms slacken, and her little fingers make starfish then clench to fists. The muscle memory of play has faded. Her mouth is a small red o. Her eyes follow little girls in pink coats as they weave and swirl around the slide and she sits, alone on the see-saw, wondering. I offer to go on the other side and bounce her in the air; she shakes her head, unable to peel her eyes from their haloes of crackly, autumn-lit hair.

When we visit my mother for the first time since we stopped visiting, she walks around the house, outlining the cabinets with her fingertip, taking inventory of the toys she last played with in March. She pulls them out of the basket by the sofa: zoo jigsaw, cat puppet, baby doll. She lines them up, then files them away, ignoring the slices of fruit on the plate my mum places beside her. We dress her in her pyjamas and coat for the drive home, and after we extricate her heavy, sleeping limbs and roll her into bed, we find one of my mum’s coasters, stashed, in a secret, unobserved moment, in her pocket.

Sure, the five months might seem negligible to me, a blip in my lived experience, and sometimes, minus the desperate pain of the deaths, it’s been fun to complete quizzes on Zoom and order at-home cooking kits from Michelin starred restaurants. We tried those places we couldn’t bring a kid to, Zoomed with friends who we thought had forgotten us, yelled and threw things at the news. And in truth, I’m already thinking about the future, about the time I’ll find a scrumpled, faded medical mask in my jacket pocket and smile, privately, remembering this.

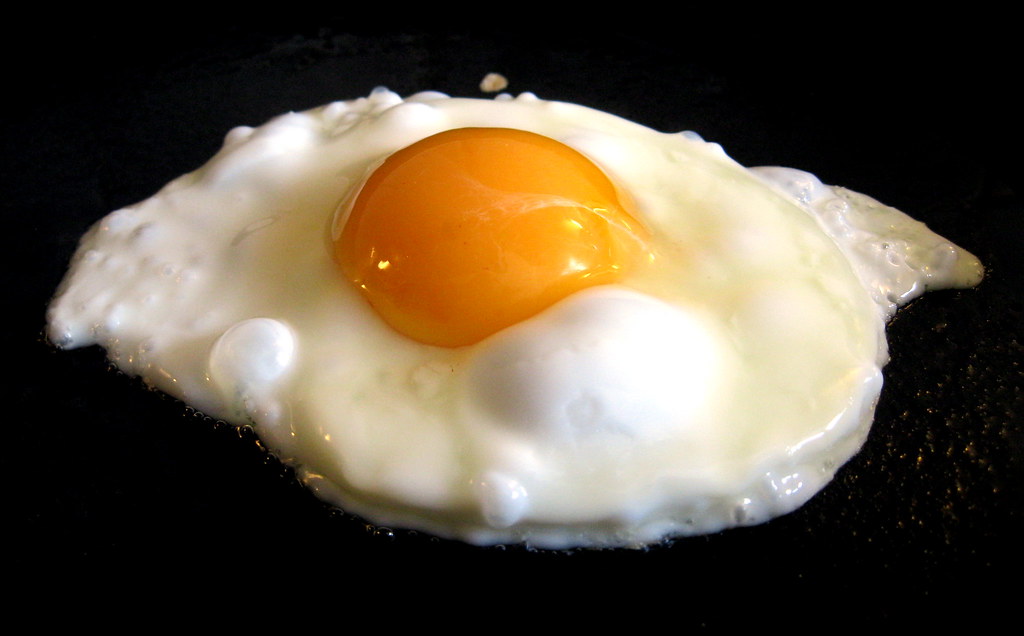

To my daughter though, the five months represents ten per cent of her time on earth; ten per cent of her life, spent alone in the house with her parents, presented with food three times a day, every day, a cacophony of colour and assortment of smells, and not eating the meals, the only thing she can control. The TV blares about PPE, shows diagrams of the virus, flashes photos of the people who’ve died as it invaded their bodies. She crosses off another once-loved food from the mental list of things she eats. All that’s left on the list is eggs: scrambled, fried, poached. Boiled and mashed with butter in a special spotty cup.

‘You’re not going to die,’ she says, through a mouthful of omelette. ‘Are you, Mummy?’

Ellie Slee is a freelance writer from the North East of England who focuses on film, feminism and motherhood. Her life writing was shortlisted for the Wasafiri New Writing Prize 2020.