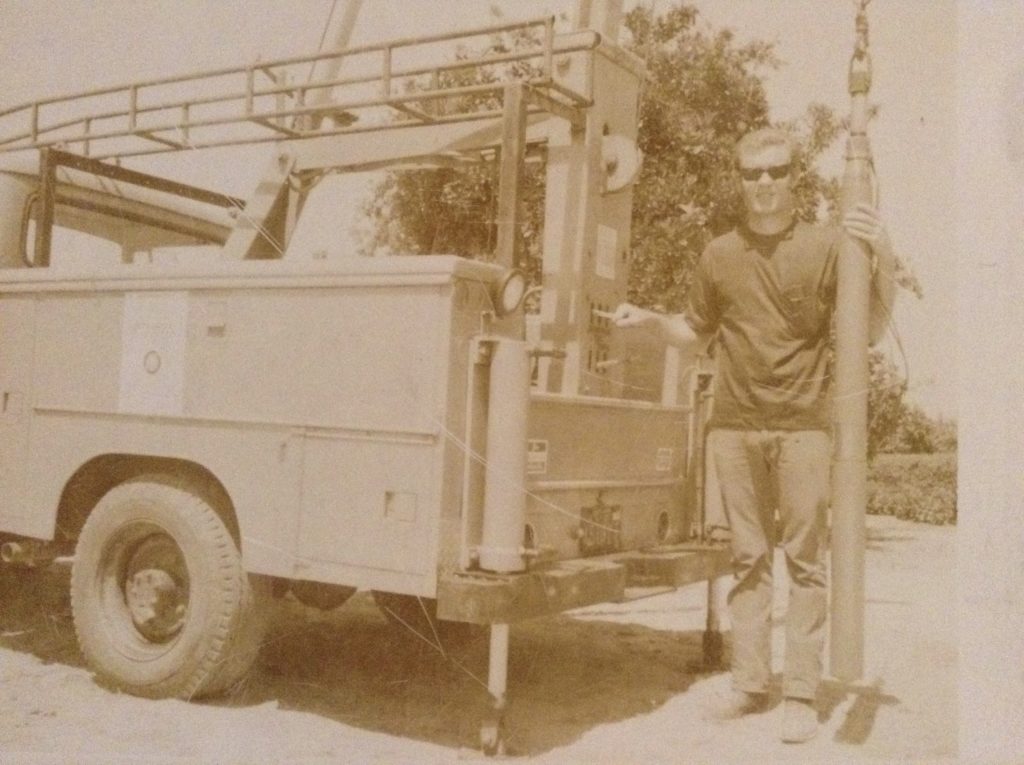

I found a snapshot of my father taken before I was born, a black-and-white print on foxed paper that makes the photograph look older than it really is. He has one hand on the levers of his pump truck, a 1959 International with telescoping boom, and with his other arm steadies a pump the length and thinness of a post that dangles from a hook at the top of the picture, the cable disappearing out of frame above his head. He looks at the camera through black prescription sunglasses; the collar of his t-shirt stretches away from his skinny neck. He’s smiling, sort of.

I barely recognize this young man, but I absolutely know the truck. The tool compartments built into the bodywork over the back wheels were filled with elbow fittings, rolls of teflon tape, jars of pipe dope; the smell of damp, rust, and solvent rushed out when the doors opened. Dust settled on the dashboard bakes in the sun. I used to spend hours behind the wheel, pretending: I remember the heavy click of the signal lever as I indicated an imaginary turn, feel the grit of the decomposing shifter in my palm as I change up through the gears, going nowhere except further into my own head.

Eight underground wells provided domestic and irrigation water to our hundred acre vineyard and five houses: we lived in one, my grandmother in another, and the remainders rented out. We were five miles from Caruthers, the nearest small town, and twenty miles from the city of Fresno, in the dry San Joaquin Valley, with no access to the network of canals, aqueducts, and reservoirs that supplied Central California’s urban areas. Our surroundings were mostly dirt. Vineyard soil as fine as talcum blew into the air, colored the horizon a shade of brown. Even the dirt avenues between vineyard plots, compacted by tractor traffic and undergirded with hardpan, would begin to break down into dust during summer’s yearly droughts. We relied on submersible pumps to put water back in the land, back in our bodies. Occasionally we’d open a faucet in the house and get a slow trickle of dirty water followed by a puff of dry air. We eliminated simple problems before diagnosing a broken pump: checking other faucets for running water, inspecting the electrical box powering the pump for a build up of dirt or nest of ants.

I must have been eleven or twelve when I helped my father replace a burned-out pump which brought drinking water to the house on King’s Place, named for the raisin grower my father had bought the land from. My father backed the truck into position over the cement slab behind the house. He lowered the hydraulic jacks to bolster its rear end then raised the boom high overhead. My job was to work the levers, six of them built into a panel at the back of the truck that controlled the telescoping boom and winch, spooling and unspooling cable from a drum inside the truck bed. I held a too-large hardhat on my head, looking up at the weighted hook swinging at the top end of all that cable.

I didn’t know what I would be hoisting from the well. Despite the hours I’d spent playing behind the pump truck’s wheel, I’d barely imagined how it might serve its intended purpose and had never asked my father. I knew he once worked for Sta-Rite Pumps, but not the details of what he did. What snaked underground below the slab and brought water upward to the houses and fields might as well have been magic to me. The best I could picture was a single silver pipe as long as the well was deep, about a hundred feet, the pump at the far end like a mouth drinking up the well water. Even now I didn’t ask my father to tell me about what we were doing: he believed that those who did not know what he knew were dim, idiotic; instead, I followed his directions, learned as we went along, and tried to act smarter than I was.

My father turned the power off at the electrical box, then knelt to remove the fittings that plumbed the underground well to the above-ground holding tank, already hot to the touch. He opened the pipe that rose a few inches above the collar of the well casing, cemented in the concrete slab. Some hundred feet below us, it held the submersible pump below the water line. His hands on the clunky pipe wrenches were practiced, efficient, and his focus absolute. The little moisture that remained in the pipes leaked out, the color of rust, smelling of iron, more like blood than water.

My father threaded a cap with a metal loop onto the pipe, attached the truck hook to the loop, then waved his arm for me to pull the lever, to take the tension out of the cable. He removed the clamp that held the pipe tightly in the casing collar. Now it was suspended by the pump truck, swaying slightly in the open well. My father gave me the sign to pull the lever again and as the winch reeled in cable a long train of water pipes began to rise from the depths. Beige, the pipes looked like soil all around us, as if the metal aged to match the place they watered. My father guided the ascent with his hands, careful to keep the electrical wires that paralleled the pipe from snagging on the casing collar, warning me not to jerk at the controls. It’s the only warning I get: pay attention, or else.

When a joint between lengths of pipe emerged, he signaled for me to stop the winch. With a special clamp my father locked off the pipe below the joint then unthreaded the length of pipe above that. I let out more cable while my father walked backwards with the freed pipe until it was almost horizontal, then he laid it on a pair of boards set in the dirt. He unhooked the hook, unscrewed the loop, threaded the cap to the next pipe locked off in the well, and started again.

This process of raising a length of pipe and locking off the next one repeated for the rest of the morning. To pass the time my father shared stories about guys he used to work with who’d snagged the wiring and started fires, who’d dropped pumps in deep wells, who’d cost their companies thousands of dollars and themselves their jobs. Hearing the disdain in his voice, I understood he was teaching me a lesson: don’t be one of them. Pay attention. Work hard. Don’t embarrass me.

When the pipes emerged coated in well water we knew we were close to the end. Finally the rusty pump emerged from the well, a fish we’d fought half the day to reel in. My father swung it away from the opening and I lowered it to a soft landing on the slab. The wet pipes dried quickly in the sun, though they’d been submerged for years, maybe decades, turning a shade of brown similar to the vineyard dirt all around us. It was the last color I’d expected the pipes to be. I knew the vineyards spread horizontally, across all those miles of flatness, but had never known, until now, how deep that same soil went.

My father disconnected the wires from the old pump and reconnected them to the new pump, silver and sleek, yet to take its first dip, with the elongated counters of a pill. He threaded a length of pipe to the pump and hooked the loop. By now, the day half gone, sweat soaked his shirt, cascading downward from his collar toward his jeans, the thighs of which were wiped with his wet handprints, though his energy hadn’t faded since morning. Mine had. The sun had warmed the pump truck levers to a temperature I couldn’t touch for long. I felt the sun like hammer blows in my head. Most of my energy went toward hiding my burning skin and softened muscles from my father.

The afternoon played out like the morning in reverse. I pulled the lever, spooled in cable, and my father positioned the pump over the well—I pushed, and the silver pump lowered, disappearing underground. The pump went deeper while the train of pipes was reassembled above. With the well capped, the holding tank plumbed, the relays wired and the power back on, water flowing again, there were no signs anything had changed. Yesterday’s coughing faucets seemed a barely remembered nightmare. My father had known exactly what to do. He knew everything, could do anything, it seemed. I thought I would need nothing else in life, ever, beyond what I learned by listening and watching him closely.

Because my father is not a still image—he’s action, purpose—this black-and-white picture is a mystery renewed each time I look at it again—until recently, when my mother told me the picture was taken in 1975, the year before I was born and shortly after my father quit his day job at Sta-Rite Pumps to grow raisins full-time. He’d only recently bought the pump truck to provide a second income in the early days of farming. In The Twin City Times, our town’s weekly newspaper, my father ran an advertisement offering his services as a pump installer. The picture appeared in a box with his name and rates. I’d never known.

Until now, the year I’ll turn forty-two-years old, I believed my father’s departure from the pump industry for the vineyards to be a clean, safe break. He had a plan. Means. He might have risked the uncertainties of change, but not of failure. Failure never seemed a possibility the way father talked. There have been many times it would have helped me to hear about the struggles he faced. Knowing that he once needed to make extra money would have been a welcome comfort when my own paychecks were running short. Instead, my father preferred to tell stories about the failures of others, people he called idiots. I drew the only conclusion his stories offered: that I too was an idiot, his mistakes mere shivers compared to mine. Whatever worries my father had about his future in 1975 remain unspoken even now. And I do not share my worries with him.

Clippings of the advertisement have been lost. Only the picture, stripped of context, remains. It’s possible my father would no longer recognize himself either, as he appeared before children, before making himself into master of all he surveyed, even the water underground.

John Carr Walker the author of the story collection Repairable Men (Sunnyoutside, 2014). His recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Gimmick Press, Shantih, Hippocampus, Gravel, Five:2: One, The Toasted Cheese, Inlandia, Split Lip, Entropy, and The Collagist. A native of California’s San Joaquin Valley, he now lives in Oregon.