When I was eight I loved wandering around the shore near the village where I lived. When the tide was out the rocks and seaweed went on for miles. One day, I was climbing over boulders covered in bladderwrack when I met a man crouching beside a rock pool. He wore shorts, walking boots and had a camera round his neck.

“Look at this,” he said. I squatted beside him. In a patch of sand in the pool, a starfish was basking, orange, gold and pink like coral. Its arms waved like fingers in a magician’s gloves. It seemed like an alien in the brown and grey landscape: I’d never seen one before.

I knew a bit about rock pools: they were sometimes deeper than they looked. The ones nearer the fields had tadpoles in spring. You could see limpets and barnacles stuck all round their edges. But this man knew remarkable things. His name was Mr Moore, and we went looking for more starfish together.

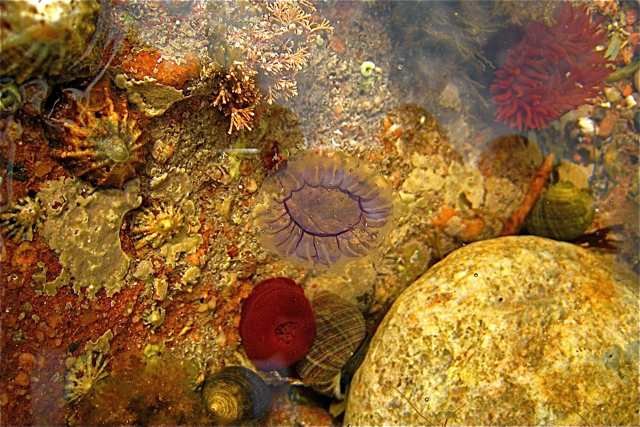

In one pool, he rippled a curtain of seaweed and out scuttled a green and grey hermit crab. In another, he showed me a blood red sea anenome clinging to the side, its fronds swaying gracefully. But when he fished it out in a net, its flesh shrank to a tender button drawn in on itself. In the water again, it waved like a feather boa.

Mr Moore liked to take pictures: he said he was a biology teacher at a school down the coast. He’d parked his van up on the headland.

He stood and suddenly kicked a gnarled old limpet off a rock. He passed it to me and its spongy underbelly oozed salt water onto my palm.

He was a magician, that man, of the water. He revealed the hidden life in those pools. Sticklebacks like ghost fish. Winkles you could collect to eat. A shrimp swimming like a question mark. So when he said he’d like to take some pictures of me, I followed him right into his campervan.

I don’t know why I was allowed to play on my own for such long periods. My younger brother was undergoing treatment for cancer at one of the hospitals in Edinburgh – an hour and a half away over winding rural roads and across the Firth of Forth. Maybe my parents were distracted. My mother was fighting her own battle: postnatal depression had broadened and deepened into something else, and she’d been in and out of hospital for courses of electric shock therapy that burned out memory as well as sadness: she could no longer remember her wedding day, much of her childhood, my brother’s birth or mine.

Inside the van was a wide cushioned seat you could make into bunk beds, a small stove and curtains that you could pull to make it cosy. Mr Moore pulled the curtains. He took the cap off his camera lens, and adjusted the curtain behind me again. He looked through the camera, looked up, pulled the sliding door half way across. He took a couple of pictures of me, as I sat on the cushioned seat, just as I was.

Then he walked round the outside of the van to the driver’s side door.

“You want to come and sit up here?”

Of course I did. I climbed over onto the front passenger seat. He closed the van door with a heavy thunk and drove me home.

“I like taking pictures of children. If you ask your mum, I’ll come and do some more,” he said.

When I told my mum about my new friend and the pictures, she wanted to know exactly what he’d done, what he’d said. I told her about his campervan, where he liked to brew tea, and how he showed me rockpools.

She muttered down the phone to my dad in the corner of the hall, a look of grave concern on her face. I suspected I’d done something wrong.

The following week, he came back, parked the van outside.

“He’s waiting for you to go out and talk to him,” I said.

Mum stood at the bay window of our sitting room, without going too near the pane to see his campervan, visible through the lilacs that lined the garden wall.

When she came back inside, drawing her cardigan around her, a decision had been made. Mr Moore would return the following week to take my picture, and my brother’s, in the house.

“You mustn’t get into his van again on your own,” mum said. I didn’t understand why.

The day that Mr Moore came to take our picture, mum told us to look smart. The chemo hadn’t affected my brother’s hair at that point: luxuriant chestnut curls grew out of his scalp at right angles. He never combed it. But for the pictures, mum gave him a parting and brushed his hair into a bouffant updo that he hated. He screamed as the brush got stuck again and again.

Mr Moore placed a kitchen stool in the middle of the sitting room, and got my brother and me to sit on it, much closer than normal. I put on my favourite dress, but it had egg yolk on the front. Mum said I should change it, but Mr Moore had an ingenious solution: he folded the dress subtly over my chest to mask the stain. My brother and I didn’t smile and he didn’t ask us to. With mum watching over his shoulder, he took a picture that became a fixture on the mantelpiece for many years after.

When I look at the picture now, I see my toothy, plump eight year old self, with huge, slightly hurt eyes, and my pale brother. I understand why my mother wanted a picture of us at that moment, especially of my brother. I like to think that Mr Moore took that shot to capture an innocence in both of us. But really, I don’t know what he saw or what he wanted. I don’t know if meeting him was a lucky encounter or a lucky escape.

I went to the shore often after that, but he was never there again.

I can still kick a limpet off a rock, but sticklebacks and starfish continue to elude me.

Ebba Brooks is a former journalist and book festival founder. These days she teaches creative writing at the University of Leeds and digital skills at the University of Salford. You can read more about her on her blog.