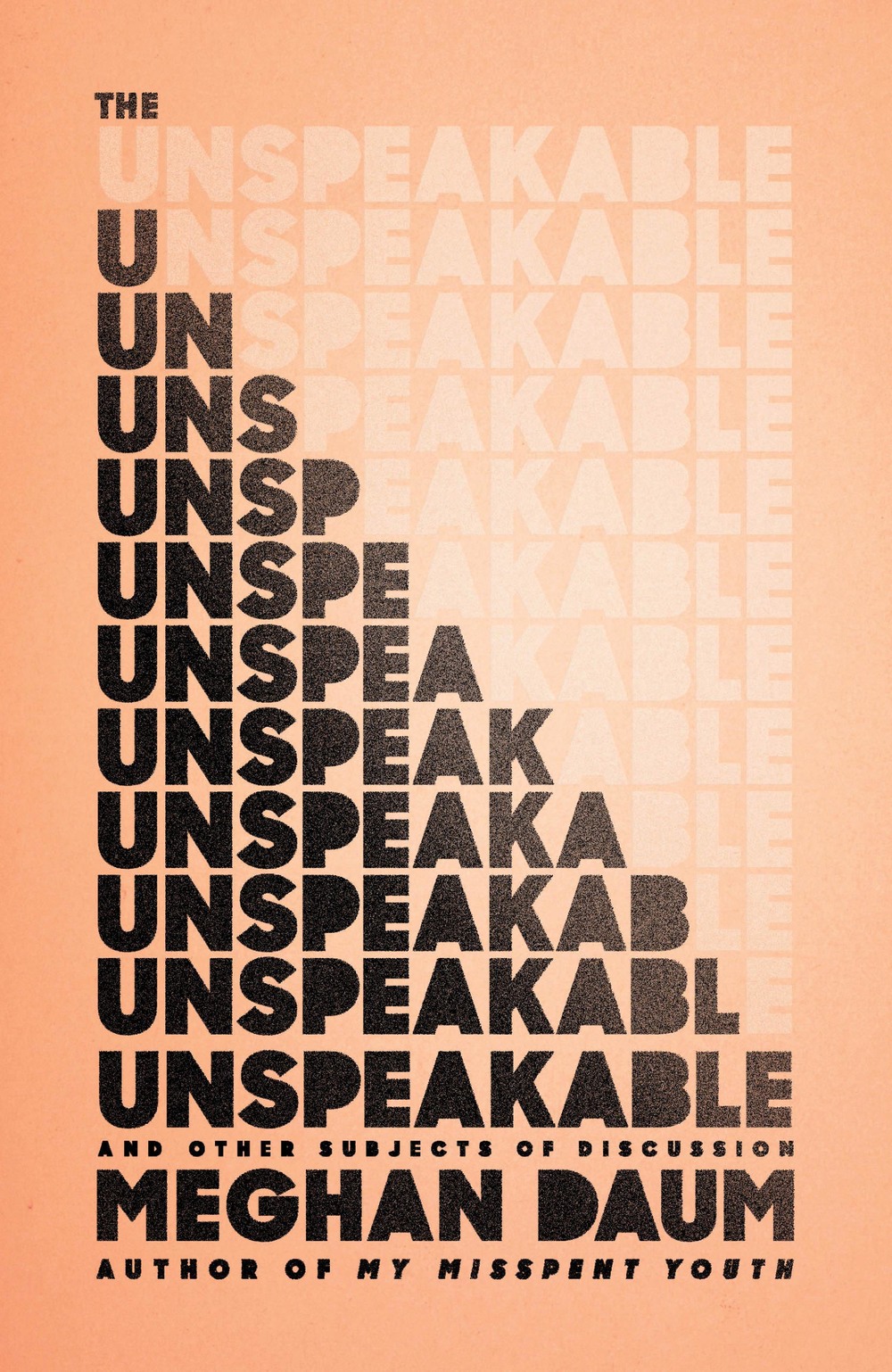

In Meghan Daum’s last collection of essays, My Misspent Youth, she captured the ambitions and anxieties of a generation of twenty-somethings. Within this collection, she mines her thirties and forties with such honest and brave fervour that I sometimes found myself taking a sharp intake of breath.

In her introduction, Daum says that whilst she was working on the collection, she told people it was about ‘sentimentality’, and that she hoped the essays would add up to a larger discussion about the way human experiences too often come with pre-assigned emotional responses. She wanted to explore the way we often feel guilty; ashamed when we don’t feel the way we’re “supposed to feel”, asserting that to reject sentimentality was practically un-American.

One thing Daum cannot be accused of in this collection is over-sentimentality. The essay opening the collection, ‘Matricide’, had me reeling from the start. It details the last few months of her mother’s life as she is being treated for, and eventually dies from, terminal cancer. A recount likely to be laced with sentimental touches and endearing scenes, right? Not so. In fact, initially, I found myself recoiling from it, wanting to put it down as I found it uncomfortable reading, not least because I’d been in the very position in my thirties, caring for my own mother in startlingly similar circumstances. The details of Daum and her brother unplugging a set of expensive lamps and packing up their mother’s apartment around her, because they didn’t want to have to pay rent on her apartment after her death, left me cold.

As the essay unfolded, however, I saw how, though our attitudes and experiences differed, the way Daum reflects on the often conflicted emotions involved in nursing a dying parent, and the honesty of admitting to wishing for it all to be over, resonated loud and clear. In her introduction, she refers to the expectations we have of the dying as being “shrink-wrapped in a layer of bathos” and it was, in the end, refreshing to read a more true account of dealing with the death of a parent. Ultimately, I found Daum’s honesty and willingness to discuss such issues in this way somewhat transgressive, and helped to unpack some of the conflicting emotions I held on the subject.

One of my favourite essays in the collection was ‘The Best Possible Experience’, in which Daum recalls her relationships with highly unsuitable, and increasingly comical, suitors over the years, concluding that waiting to marry in her forties was the right choice. There is a heavy dose of humour when Daum is outraged at being called a romantic by an audience member at a lecture she gives about the dangers of delaying marriage rather than settling for less than perfect relationships. After reading this essay, I wanted to be Daum’s best friend, to pull up a bar stool and listen to her talk all night long.

With essays covering such diverse subjects as death, marriage, ageing, her mistaken identity as a lesbian, mentoring kids, Joni Mitchell, her loathing of cooking, miscarriage, how her sentimentality finally kicks in when it comes to speaking about the love of her dog, and playing charades at a party of Hollywood celebrities given by Nora Ephron, it is tricky to attach an overarching theme to these pieces of writing. Perhaps this points up the difficulty in grouping essays originally written for individual publication or columns into cohesive themed collections. Many of Daum’s essays have appeared in publications such as The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and Vogue, as well as her column for the Los Angeles Times. Perhaps life choices would be one theme, as her decision to not have children is brought up several times, and at one point I felt her veering towards sentimentality, when she writes: “There is nothing I’ve ever been sorrier about than my inability to make my husband a father.” Daum is clear, however, that she has never wanted to be a mother, and entertains endearing fantasies of a future phone call where a long-lost child of her husband’s turns up from some forgotten one-night stand, and he can be father to a full-grown child without her needing to participate in the child’s creation.

I would recommend Daum’s collection of essays as a refreshing, original discussion on some difficult subjects, often handled with a stroke of humour. I am doubtful you will read a more honest, nor ultimately likeable, essayist than Daum.

Kate Jones is a freelance writer based in her home city of Sheffield with her husband, two feisty daughters and their spoilt cat named George. She has recently completed an English Literature degree with the Open University as a mature student.

She divides her days between writing features for online magazine Skirt Collective, reviews for The State of the Arts website, and reading books for review. In between this, she indulges in her favourite writing habit of creating flash fiction, and has been published in various literary magazines, including SickLit, Gold Dust, and Spelk, as well as being nominated for this year’s Pushcart Prize. You can also find her writing on her personal blog.