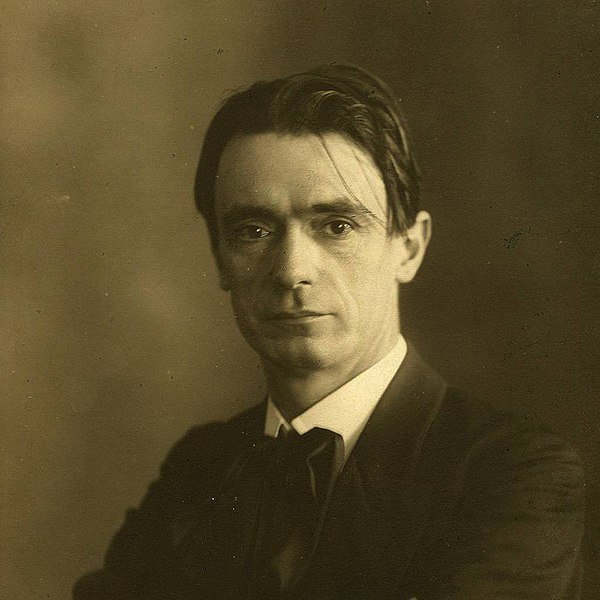

You could barely move, in fin-de-siècle Mitteleuropa, without encountering something mystical, transcendental, or at least a bit occultish. From Rilke to Madame Blavatsky, counter-Enlightenment was in the air — or, possibly, had leaked into the water supply. At any rate, it had managed to make its way up the Danube and into the sleepy Austrian village of one Rudolf Steiner, who at nine years old had already begun communing with a dead aunt and detecting visions of the spiritual realm within the pages of his geometry textbook. By 15 Steiner had attained a complete concept of time, although admittedly he still had a few questions. At 19 he was journeying by train to Vienna when he met a herbalist who invited him back to his cottage. Although the crockery on offer was sub-par — no cup was provided and Steiner was forced to slurp his coffee from a bowl — he nevertheless managed to glean from the fellow the answers to his remaining metaphysical quandaries.

And after that, there was no stopping him.

#

Leaving behind the hubbub of the street and stepping through the arched wooden doors of the college is something akin to entering an idiosyncratic and possibly clandestine church. Its ceilings rise and fall in sculptural double curves. Men and women attired in rumpled linen and ergonomic sandals move purposefully through the hallways. The walls are daubed a shimmering, ethereal peach, and on them hang intricate coloured tapestries depicting scenes of mystic import. Sometimes voices echo down the staircase in medieval plainchant, or Celtic folk song. It doesn’t take long to realise there are no computers.

I’m here because I’ve just dropped out of my PhD and have decided, on a directionless whim, to train as a teacher in Steiner’s alternative school system. I have almost no knowledge of anthroposophy — the esoteric philosophy on which the schools are based and which Steiner developed as he matured from penniless student into prodigious writer, lecturer, and eventually head of his own quasi-religion — beyond an introductory book I’ve recently ordered from Amazon. (Rooted in German idealism and mysticism, anthroposophy underpins a spiritual movement which grew to encompass not just education but also agriculture, architecture, holistic medicine, the arts and even banking.) True, I have one or two pesky doubts, but I brush these aside and choose instead to focus on the pictures I’ve found online of charming pastel-coloured classrooms and merry youngsters digging organic gardens. I know the schools have a reputation for being hippyish places that foster children’s creativity and imagination, and that’s all the information I need to forge ahead with my new life plan. There are several red flags in the book to suggest that a profession based on what Steiner called his ‘spiritual science’ might not be an ideal fit for me — references to Rosicrucianism, to repeated earth lives, to the lost kingdoms of Lemuria and Atlantis — but I’ve blithely paged past every one of them. Teaching is the only idea I’ve got right now, and I’m pretty sure I won’t be able to hack it in the overheated state system.

On the first day of the course, my fellow students and I troop into the college’s wood-panelled hall, where we are invited to arrange ourselves into a circle and meditate upon a vase of twigs that has been placed in the centre. Then a woman in an earth-toned tunic introduces herself as Kitty and begins a welcome speech. Clasping her hands, she lists the manifold evils of modern technology. The orange-trousered man beside me opens his notebook. But the iPhone is just the tip of the iceberg, she continues, motioning to the window. The world out there is broken. The special task of the Steiner teacher is to lead the next generation back to wholeness. Around the circle, heads nod. And in order to accomplish this, Kitty explains, we’re not going to be learning the sorts of things one would expect to find on a mainstream teacher training course. Those things are not what the world is crying out for; they have failed us. Instead, we’re going to be studying wet-on-wet watercolour painting and eurhythmy.

What is eurythmy? Eurythmy is interpretive dance.

#

Its inventor was Steiner’s second wife Marie von Sivers, a Russian aristocrat who disliked the innovations of the modern theatre and in response developed an earnest and very weird form of movement which sought, for some reason, to make speech visible through gesture. I soon discover that under no circumstances will we be permitted to perform to music. Instead, we are accompanied by our instructor Renata’s declamation of verses on topics such as the abundant beauty of autumn leaves and the Archangel Michael’s heavenly defeat of Satan, recited emphatically in her Teutonic baritone. Renata attempts to teach us to express, using our bodies, the full spectrum of the rainbow, the ‘soul feeling’ of the letters of the alphabet, and the four medieval temperaments. Steps must be performed in complex group formations, absolutely none of which I am capable of mastering. “No!” she shouts, her helmet of gunmetal grey hair oscillating in exasperation as she repositions my arms for the third time. “Vee are today very phlegmatic! Show me instead choleric! Now step, step, step to ze left!” I look confused. “Like ze colour red,” she adds, helpfully.

In the Spring, we pile onto a stuttering minibus and drive deep into the countryside for a Steiner-themed sports day. It opens with what has become the familiar circle-on-the-floor lecture, where we are informed that anything to do with the feet is the domain of Ahriman (a destructive spirit appropriated by Steiner from Zoroastrianism) and for that reason, football is off the menu forever. A fervent young coach grows increasingly irate at my inability to jump through a moving skipping rope, an exercise to which he ascribes a great deal of importance. He takes me aside to let me know that if I would only remove my glasses, I would be able to see much better using the sensory perception organ of the soul. I assure him that I very much would not: I am in grave enough danger of sustaining a rope burn to the face as it is. The sensory perception organ of the soul is no match for my astigmatism.

By now I am all too aware of the infeasibility of my ever becoming a Steiner teacher, but unable to admit that I have blundered my way into another dead end of a life choice, I continue to haul myself to the college to play my wooden recorder, make pictures of gnomes with beeswax crayons — Steiner had a particular affinity for these diminutive humanoids, and taught children that they were real — and rectite Norse poetry. But of all the tutorials, my least favourite is clay modelling. Once a week, we lug trestle tables from the cupboard and arrange them into a horseshoe around the hall. Then we queue to dunk our hands into buckets of sloppy reddish clay, which we carry back in dripping lumps to our places. The instructor, Eugene, a wispily-goateed man in a wraparound pinny, begins the guided meditation. “Close your eyes,” he whispers. “Fold your hands over the clay, as in prayer. You are walking up a path. The path is winding. The path is dark. But! You come across a gate. Push it open! What do you step into? That’s right, students! You step into the light. Now, form a perfect dodecahedron. You’ve got an hour.”

#

As a student in Berlin, the writer Stefan Zweig encountered Steiner, twenty years his senior, in a society of young artists and intellectuals who met weekly in a coffee house. Zweig describes the ‘hypnotic force’ of Steiner’s eyes, and was interested enough to go to a few of his lectures, which left him ‘both full of enthusiasm and slightly depressed.’ (Zweig does not elaborate on the cause of either the enthusiasm or the depression.) Decades later, Zweig was still murky on what exactly Steiner’s philosophy was, and concluded that its allure arose ‘not from an idea but from the fascinating person of Rudolf Steiner himself.’ In 1925, Steiner died in bed at his temple in the Swiss countryside, overworked and exhausted from his manic lecture tours and the unceasing demands of leading a spiritual movement by now numbering thousands of members. Marie, dedicated as ever to the cause, was out of town with her eurythmy troupe. She arrived home a day too late to witness the moment of her husband’s passing from this life to the next.

#

Mostly out of stubbornness — I’m a Capricorn — I make it almost to the end of the year, but after digging into some of his more unpalatable writings that lurk online, I finally accept that there is nothing salvageable of my plan to teach in a Steiner school. To give him his due, Steiner was a polymath who attempted to enact real social reform in the wake of the devastation caused by the First World War. His education system was revolutionary in its time and contains much that is positive — I’ve no doubt that it really can foster children’s imaginations and creativity — even if I am ill-suited to its unique proclivities. And whilst Steiner’s heart was usually in the right place and some of the work undertaken by the anthroposophical movement admirably pioneering (such as the earliest form of modern organic farming), it is an unfortunate fact that chunks of his philosophy remain at best silly and at worst racist, sexist and pseudoscientific. When I raise my concerns with Kitty, she counters that I’m dwelling too strongly in the intellect and prescribes more recorder playing. I leave without collecting my watercolour paintings.

#

But though I never graduated, my sojourn in the realm of anthroposophy has left its (mysteriously indelible) mark. There’s my wardrobe which, ten years on, has never fully recovered — I’m partial to a linen sack dress. I kept the beeswax crayons, too, and my set remains in use to this day. Then there’s something else, something more difficult to explain. It’s the doubt that rears its head when I muse on our current situation vis-à-vis the strangled death throes of late capitalism: did Steiner, with his gentler, more holistic approach and his biodynamic beans, have a better way? When the doubt surfaces, I squash it down, hard. Because somewhere in a parallel universe, Kitty and I swirl hand-in-hand, our voices raised to the astral plane in song, and the song is about gnomes.

Bibliography

Lachman, G., 2007. Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Steiner, R., 1967. Correspondence and Documents 1901-1925. Translated from German by C. & I. von Arnim, 1988. London: Rudolf Steiner Press.

Steiner, R., 1928. The Story of My Life. Translated from German by H. Collison. London: Anthroposophical Publishing Co.

Zweig, S., 1942. The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European. Translated from German by A. Bell, 2009. London: Pushkin Press.

Holly Aszkenasy lives & writes in London. Her newsletter about things that don’t go to plan is Ever Failed. She tweets @hollyaszkenasy