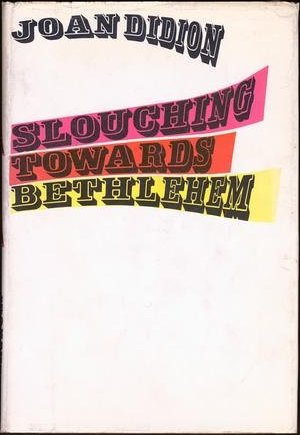

At the tender age of 22, Joan Didion won a Vogue essay contest. It was 1956, decades before the advent of reality-based meritocratic TV job competitions that are so familiar to us today. Nevertheless, her prize was a job at the magazine, and a cross-country move, from her home state of California to New York. During her years in NY, she met the man who would be her husband for 4 decades, and she eventually moved back to California with him. She had a job in New York, writing for Vogue before she graduated from university. With her first collection of nonfiction essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, she became a star of New Journalism, the subjective style that started in 1973 and changed nonfiction writing forever.

And if that was all you knew of Didion, if you have never read her essays or memoirs, you would think she had a charmed life.

But in her nonfiction, her essays and memoirs, you meet a woman much more ordinary, a person who struggles with worry and self-doubt, enough to know what it means when you’re up all night, wincing through memories of the times you’ve done wrong. In her stark and severe essay On Self Respect, she strides (rather than wanders) through embarrassment and cowardice to one of the clearest statements regarding human society I’ve ever read: “The dismal fact is that self-respect has nothing to do with the approval of others – who are, after all, deceived easily enough…”

This sort of sharp clarity especially marks Didion’s early essays. In Marrying Absurd, an 1967 essay about the Las Vegas wedding industry, her writing draws us quickly into the frankly bizarre situation that is Las Vegas. There is no rambling about with her. She is in Las Vegas, where there is no sense of time and “… neither is there any logical sense of where one is. One is standing on a highway in the middle of a vast hostile desert looking at an eighty-foot sign which blinks ‘STARDUST’ or ‘CAESAR’S PALACE.’ Yes, but what does that explain?” Her style is so immediate. When I read this sentence, I am on the highway with her. I am exasperated with her.

And the clarity of her writing only accentuates her deep, critical analysis. Didion is a tough thinker. When I first read The Women’s Movement, her eviscerating less-than-five-page dismantling of all second-wave feminism, I was maybe 23 years old. I knew something was wrong with feminism when it seemed to be so trivial. Whether or not a woman changed her surname and how many times she had to do the washing up per week never piqued my interest. In this essay, Didion breaks down the problem of second-wave with sarcasm so sour, it stings.

Her most recent memoirs sting, too, but in an entirely different way. The Year of Magical Thinking is about the year Didion spent mourning her husband and taking care of her daughter through a life-threatening illness. Joan Didion’s ability to stare unflinching at the hardest, most terrifying parts of life, is what makes her writing so important. No one else does quite what she does. And she thinks hard. And through reading her work, you can tell that didn’t come easy. To think she’s had a charmed life is to be what she never is: a soft, unclear thinker.

Joan Didion’s books and essay collections are available just about everywhere. The essays mentioned in this article can all be found on this fantastic website, which is quickly becoming a favourite haunt of mine.