Station One

In September 1996, my Dad turned 40. On that birthday he stared into our fireplace and decided that he was no longer a Christian. He’d been harbouring doubtful thoughts for twenty-four church-going, bible-reading years, during which time we had all been dutiful members of the local parish. But Dad’s faith had been challenged one too many times. This was his Gethsemane moment, but this time God lost because he didn’t exist. Dad did exist. Dad was very real.

The gas-effect flames nodded. Thus, Dad was condemned.

Station Two

Dad’s one true religion was, and still is, the theatre. His God is Bacchus, his holy spirit the twin masks of comedy and tragedy. Shakespeare his Jesus, Sophocles his Moses.

By 1997, he had been a Drama teacher at Cardinal Newman College in Preston for ten years and wanted to mark the occasion with a special showcase production. As something of a farewell to the last ailing remnants of his faith, he chose to stage The Mysteries, the medieval plays which cover everything from Creation to Revelation in three cycles of glory and hosanna. Basically: the theatricalised bible stories.

Station Three

The students form groups and each group gets a story. The general feel of the production is Italian Renaissance. The college is very happy, the students are excited, my Dad is content.

But Bacchus, the Greek God of Theatre who is also the God of Wine, is restless. Things are too safe.

The group with the nativity story hit a snag. Everything is too tea-towels and little donkey. Wobbly crowns and tinsel halos. So, the students get radical and modernise it. The nativity is shifted from Bethlehem to Belfast, from year 0, to 1997. Bacchus gives a wry smile.

The thread of logic spools out: if Jesus is born in 1997 then he would die in 2030. This, therefore, is the second coming. Dad has already cast his best actor in the role of Jesus for the Passion story. And now, in the flicker of an instant, this Jesus becomes a near-future messiah.

The actor’s name is Lauren. She just so happens to be female. For the students the next step is obvious: He has come back as a She. Jesus becomes Jessica.

Bacchus downs his wine. Dad falls for the first time.

Station Four

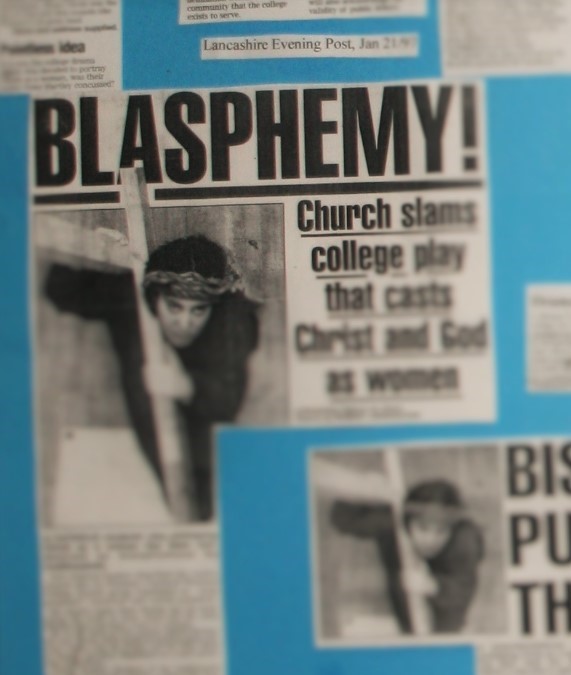

Dad puts out a press release to the local media. He is proud of his female Jesus; her picture leads the triumphant herald. The media are quick to respond. Very quick. Too quick.

Station Five

The Headteacher of the college is delighted. The chair of the board of directors is fully in support of the production. The chaplain is…not sure. Other eyebrows raise and then furrow, then bristle.

The rehearsals continue in earnest. Lauren learns her lines. She does so quietly, in her bedroom, where no-one can hear her delicate feminine throat desecrate the divine words of Mr Man Christ with his sacred penis and his sacrosanct balls.

Station Six

My Dad married my Mum when they were in their early twenties, a good and proper church wedding. Their first born child, my sister Jenny, was diagnosed with autism when she was two. Jenny became a trial but was one that brought our family closer together rather than driving it apart. As parents and siblings of Jenny, we learned important lessons of tolerance and respect for difference. We were hard-wired into understanding how to be patient, how to listen to the viewpoints of others, however obtuse or surreal. Mum and Dad were always liberal, tolerant, generous people but Jenny redoubled and refined that attitude. And her crazy side only made us all more creative and, by the same extension, defiant in the power of the things we made.

Complaints and damnations began to flood in. My Dad’s name is Peter, and he was as defiant as a rock.

Station Seven

Barricaded in the Headmaster’s office, Dad takes calls from all over the world. Some are supportive, including the call from Rome, which comes from a feminist filmmaker rather than the Sistine Chapel. But most of the calls are angry, angry, angry. Affronted Christians splurge their disgust. Concerned parents demand their children be removed from the show. Priests condemn my Dad to an early grave and the depths of Hell. This is 1997.

And then Lauren’s father hears the story on BBC Radio Lancashire. When he gets home, the day’s copy of The Citizen – Preston’s widest circulated free newspaper – declares BLASPHEMY on the front page. Beneath is the promo picture of Lauren herself, wooden cross resting on her shoulders. He confronts his daughter. He picks up the phone. He wades in.

Lauren’s father is the Chair of the local branch of the Baha’i church.

Station Eight

The students rally. Some of them write into the comments page of the local newspaper to defend the production. Their views are counterbalanced by the older, more experienced members of Preston’s religious community, whose argument largely amounts to ‘Political Correctness Gone Mad’ which, back in 1997, seemed to be all you needed to say to crush the rebellious uprisings of minorities.

But Dad has taught his students well. This is the theatre’s one true role: to challenge, to offend, to threaten. The rehearsals continue. The passion of the Christ gets a hell of a lot more passionate. Mary Magdalene becomes a rent boy called Mario.

Station Nine

Our living room is politely invaded. Warmed by the same fire which swallowed my Dad’s faith a year earlier, the Baha’i councilmen sit with my parents and discuss the production. Everything is very civil. Cups of tea have been made, there’s a plate of hobnobs. We don’t check the packet; some of them might have been made by women. The councilmen don’t seem to mind.

In this peaceful, patient atmosphere, a compromise is reached which satisfies both parties. Bacchus and the One True Christian God share a limp handshake. The show will go on, but with adjustments.

Station Ten

Much to her own disappointment, Lauren is one of these adjustments. She stays in the play, but is downgraded to a nameless character and a different actor takes her place. But Dad wins the greater argument. The new actor is called Harriet. She is also female. Jessica Christ remains in place.

But the show cannot be sold to the public, so the promotion is halted and the production is held privately in-house for other students and family members. For such a small scale college show, that was pretty much the audience they were expecting in the first place.

The final compromise is obligatory open discussions between cast and audience at the end of each show. The students ready themselves for an intellectual fight which never comes. Everyone agrees the production is excellent and the least offensive thing ever.

Station Eleven

On Dad’s 41st birthday he stares into the fire and reflects on the year gone by. The palms of his hands are still sore from the nails that were repeatedly hammered through them. The rest of his agnosticism drains from the wound in his side.

Station Twelve

Dad sits myself and my brother down in our bedroom and explains why he doesn’t come to church anymore. I’m 12, my brother is 7, we are both altar servers, we both say prayers. Dad explains it all as best he can. He says he cannot be part of an organisation that does not see women as equals. Behind all the bluster, scripture, belief, it’s as pure and simple as that.

Station Thirteen

For me, the experience was not a devastation, nor was it a revelation, but I do remember the raw slap of it all. The sudden realisation that a hell of a lot of people beyond our quirked family unit didn’t think in the same way we did. It was the first time, I think, that I felt real incredulity. Perhaps the timing was fortunate. On the cusp of puberty, I was shown how the girls I had recently started fancying were growing up in a world that still had a long, long goddamned way to go to reach anything close to equality and balance.

But alongside this I also felt an enormous pride in my Dad. A champion of what he believed in. An outspoken and passionate leader of young minds. A righteous and patient rebel in a stifled, rigid world. He may have been branded a heathen and damned to burn, but he had risen out of the slaughter with his head held high and his new faith in rational humanity restored and redoubled by the triumph of his students.

He still teaches, and he tells this story every year. He frames it not as a bad experience, but as proof of the power of theatre to shock, amaze and intoxicate. A power that rests in everyone’s hands as long as they have a space they can call a stage and someone to watch and listen.

Station Fourteen

In 2012, fifteen years later, the Church of England hold a very public vote to decide whether women should be bishops or not. They vote no.

David Hartley is a short story writer and performer based in Manchester. His fiction likes to tickle against your bone marrow and suckle on your ear drums. In short: odd but strangely pleasant. His latest collection of flash fictions ‘Spiderseed’ is out now with Sleepy House Press and available to buy here. This is his first proper foray into Creative Non-Fiction although he does blog regularly at davidhartleywriter.com where you can also find links to his other adventures. He’s on twitter, disguised as a rabbit: @DHartleyWriter

He read ‘The Fourteen Stations of Blasphemy’ at The Real Story’s joint Christmas event with the First Draft cabaret group in The Castle Hotel, Manchester on December 21st 2015