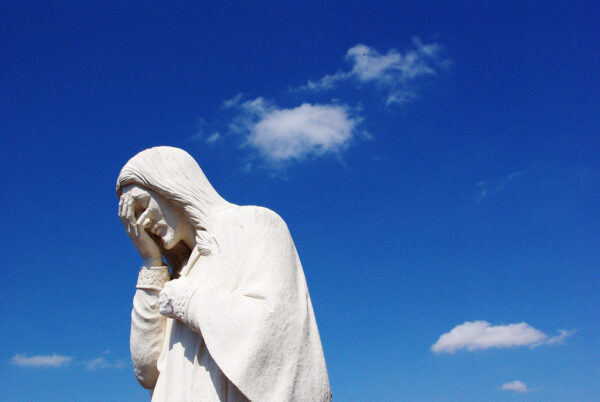

“You snowballed me!” she said through tears. You betrayed me. You shamed me. You broke my heart. “You snowballed me.” In sixth grade, after a school assembly, my classmates and I watched a woman – our sixth-grade teacher – unravel. I’d never seen an adult break down before. I did that day. I didn’t like it. And I knew that my actions, my behavior over the course of my sixth-grade year brought it on. Not mine alone, of course, but that doesn’t change a thing, wash away guilt or shame or responsibility. Every ounce of snow – shifted by gravity or sound – creates an avalanche.

We sat quietly at our desks, sad and remorseful and shamed. No one spoke. We should have. Someone should have. I think my friend, Avak tried. In an effort to salvage his well-known reputation as the smartest and most-respected student in the class, may have. It might have been him or someone else, a kind young girl, maybe, who attempted to save our teacher from a complete heartbreak and the meltdown that had already begun in front of us.

“But, Mrs. O—” someone said, her hand raised in the air, an attempt to be respectful but not waiting to be called on.

She put her hand up in the air to silence her, cutting them off. Unlike the first eight months of the school year, the student actually listened and stopped speaking.

“No, no, you have all said enough. You’ve done enough. You’ve snowballed me,” she said. Her tears fell first with real sadness and then shot out of her eyes with anger when my fellow student tried to explain what had happened. “Shut it! You snowballed me,” she repeated.

Her eyes, her stare, her running mascara, she was done with us, no matter what any of us said. She would not be gaslighted by a bunch of twelve-year-old children anymore.

The unraveling of Mrs. O continued for another, what seemed to be an hour, but was probably only 15 minutes – the gnashing of teeth, tears, the opened question of why we do this to her when she only wanted to be a good teacher – and most of us, those whose actions were of little shitheads spurred by crowd mentality but whose hearts cracked to see her cry, dropped our heads down, shifted our glances from side to side to see how our friends reacted, only to catch shamed eyes fall toward the desk.

For 13 years, from kindergarten to high-school graduation, we were a loud, unified class. Even the quietest among us shouted loudly when we collected our voices for pep rallies or Christmas recitals or snowballing our sixth-grade teacher. Giving us praise for our loud group voice would add to our bravado, reinforcing our need to go to the extreme. This was a mistake.

Once, during mass, we punctuated the last word of each line with a hard stop for They Will Know We Are Christians. “We are one in the spirit, we are one in the LorDDDD.” I have no idea who added the super hard D to the end of Lord, but the movement caught fire quickly, and by the time we hit, “And we pray that our unity will someday be restoreDDD,” somehow, we all knew what to do next. Scream! Our singing drowned out the rest of the classes in the small auditorium on the second floor of the old brick building beneath the skyscraping peaks of the Rocky Mountains.

It could have been our principal, our music teacher, or our teacher, but I know they wished they wouldn’t have done what they did. They gave us a nod of praise for our singing unto the Lord with so much gusto. Whoever it was, smiled at us and let us continue singing. This was dumb on their part. They poked the proverbial bear, and he was ready to roar. When the refrain came around again, we shouted as loudly as we could. If a photo had been taken, it would not have shown middle-school kids singing with their mouths open wide like those creepy wooden caroler dolls whose mouths look like anal sphincters. Instead, it would have shown some of us leaning back and shouting upward to the ceiling, others leaning over the poor third graders in front us yelling in their ears as loudly as possible, and still others gathering a breath to yell, “And they’ll know we are Christians by our love, by our love, yes they’ll know we are Christians by our love.” The windows chattered like teeth, and our feet pounded the floor, shaking its foundation.

The priest looked out toward us, stunned at how quickly we organized.

Teachers tried to quieten us down. They raised their hands in the air and gave us the internationally understood signal to bring it down a notch by waving their hands up and down, palms toward the floor. Some put their fingers to their lips to quiet us. But we were only on verse one, and we had a few more to go. We all understood something in that moment. They had lost their power because what we were doing could be translated as pure spiritual excitement. If they tamped us down, they could extinguish our outward love of God, even though we knew we yelled solely to be obnoxious. We manipulated the system. We ignored Mrs. O, in her first year trying to control her students. We raised our voices and stomped our feet and sang until we deafened the ears of the children around us.

When asked about it after mass, without skipping a beat, someone responded for us all, “We love Jesus, is all,” and we could never get in trouble for that. More mistakes were made, however. The song kept appearing on our mass handout, mass after mass after mass.

Having been in a faculty room and having been a part of multiple faculties before, I know there are rivalries, I know bad blood exists between fellow teachers, and I know that games are played. This must have been the case because after that day, They’ll Know We Are Christians appeared on our tiny printout for our mass’ song list more often than it didn’t.

No matter what they tried, we yelled and screamed and got away with it because they could not argue against, “We love Jesus, is all.” Were we irreverent? Not necessarily. It’s not like the time we sang the Battle Hymn of The Republic for the principal, swapping in the words, “Glory, glory, Alleluia, teacher hit me with the ruler. Hid up in the attic with a semi-automatic…,” which if sung today in the United States would take on a completely different, shocking, and devastating cultural significance, but this was the early 80s, long before our nation fell to school shooting tragedies and heartbreak. We weren’t irreverent, but we sure as hell weren’t shouting in reverence. To be honest, looking back it at, we were solely shouting because it was fun, not to hurt anyone.

The day before we snowballed our teacher, the day before she broke down and cried in anger and sadness before her sixth-grade students, we shouted something different, something innocent, during our school assembly, but it would be misinterpreted.

Mrs. O had been sick for a few days leading up to the assembly. In her place, Mrs. Hasratian, a substitute we adored because her son was in our class, and because she was the the cool mom who styled her hair and didn’t wear mom jeans. She also had a way with kids that few teachers had. She could be stern, smart-assed, and direct, all without damaging the fragile egos of twelve-year-old boys who think they know it all. Instead of “putting” students back in their place with anger and vitriol, she could gently escort them back into their place with sharp wit, and convince them – make them believe – that it was their idea all along to behave and listen, which they should.

We adored her as our substitute in sixth grade, so when the principal announced her name and thanked her for stepping in to cover Mrs. O’s class while she recovered from the flu, we cheered loudly in our “You Know We Are Christians” shouts – organizing and vocalizing quickly. What we didn’t realize, or notice, was that the way in which the principal phrased the announcement, we could be seen as real big assholes, and that’s how it happened.

“Mrs. O is out sick, but Mrs. Hasratian has been able to step in for the sixth grade,” something to that effect. It could have been switched the other way syntactically, which now, might make even more sense, “Mrs. Hasratian has stepped in to teach sixth grade this last week. Mrs. O has been sick, so she couldn’t make it to the assembly.” Either way, I know one thing. We cheered because we loved our substitute not because Mrs. O was sick. But this was it. This was the massive snowball. Someone had told her that we cheered because she was sick, that we used our singing and shouting voices that usually end with “they know we are Christians, BY OUR LOVE, BY OUR LOVE!” to cheer her illness and her absence. I would have been hurt too, if I were her.

But as they say, this was only the last boom on the mountainside that starts an avalanche.

This all began months earlier.

On the first day of class, our very excited, first-year teacher stood in front of us and said, “Repeat after me, ‘ohayou gozaimasu.’ This means good morning in Japanese.” Proud of her heritage, excited to share it with us, she repeated herself again. The class, too, I believe, as I know I was, had gotten excited to repeat ‘ohayou gozaimasu’ and so we did, all together. The first morning of the first day started off brilliantly, and, from what I remember, our young teacher smiled back toward her new class who had just embraced her Japanese language and said good morning to her in it. She smiled. She bowed with her hands clasped together as if in prayer, flattened at the palms and fingers.

Now try, “Konnichiwa. This means ‘hello’ in Japanese.” Again, the class repeated, respectively. Personally, I remember feeling excited to learn Japanese, to listen to our new teacher speak Japanese to us every morning, to try something new, and just like I had glanced at my friends and fellow students nine months later and saw shamed faces drip down toward their desks, I saw their faces mirror mine in excitement that first day of class too.

We liked her. We were glad to repeat konnichiwa and ohayou gozaimasu as long and as many times as she asked us to. This beat the hell out of reading about dead presidents and learning about the bullshit our history textbooks told us about Columbus and his friendly “konnichiwa” to the Native Americans or Cortez’s friendly “ohayou gozaimazu” to Montezuma. Our textbooks didn’t cover the Japanese internment camps of World War II in Missouri and Washington state and California. If they did, maybe things might have been different once the bell for recess rang that day and we flooded out onto the blacktop and grass to run and play and squint and pull our eyelids thin by tugging our skin and yelling, “Konnichiwa! Ohayou gozaimasu! I’m Mrs. O,” because that’s exactly what happened.

This was the 80s, and in Utah, I guess, being little racist bastards was okay. It wasn’t. I know that. But no one was going to stop us. And by us, I mean the boys of the sixth-grade classroom. I don’t have one single memory of a girl running around and squinting her eyes, but I have a flood of images of little white males pulling at their lids and saying, “Konnichiwa, Konnichiwa!” Did Mrs. O ever know this, that little boys made fun of her that day. I can’t answer that question, but I think I can take an accurate fucking guess.

The classroom unraveled in front of her, just like she had done at the end of the year. With most first-year teachers, at any level, they come in with hope. Hope to be kind. Hope to be fair. Hope to widen eyes. Hope to inspire. Hope to entertain. Hope to mentor. Hope to create a lesson plan that pulls children in and makes them want to learn, and it would all begin with something fun and new, like, “Ohayou Gozaimasu, class!”

She may not have heard or seen the children mocking her on the playground, but she must have heard it in the boys’ voices, if their intent was to be mean or to just replicate Bruce Lee or other Asian actors from famous Karate movies, mainly The Karate Kid’s Mr. Miagi, by hammering on their consonants to try to sound more “Asian” in their delivery in class, because the Japanese lessons stopped abruptly one day.

And then students, many of them, just stopped listening to her. She had lost the class.

I have lost classes. Once they’re lost, they’re lost, and it becomes a struggle to teach, every day, every week, and every month.

That day, the day she finally broke, she had misunderstood our intentions. We did not mean to hurt her, but it didn’t matter. We aimed to cheer for our substitute, the mother of one of our friends, a woman I had grown close to over the years, but a year of shitty pranks and ignoring Mrs. O when she asked us to be quiet and making fun of her in the hallway had led up to that moment. It didn’t matter what we did or did not do purposefully to ‘snowball’ her that day, she had already broken — hurt. We had thrown the thickening shards of ice at her since the beginning.

“You snowballed me!” she said through tears. You betrayed me. You shamed me. You broke my heart. “You snowballed me.”

When the recess bell rang, when we ran out of that classroom, I felt shame. But it only took a minute before some boy to yell out with his hands over his eyes as if he were crying, “You snowballed me!” and that had somehow turned our shame to laughter. It hid it way. It covered it up. It blanketed our shitty, racist actions with a cover of jokes. Her breakdown, her vulnerability had made it all worse.

Young boys can be complete and utter assholes. I was one of them. Did I ever make fun of her, I can’t remember, but I can sure as shit say that I didn’t stop anyone. Regret, it lives with me.

Mrs. O never taught again.

They will not know we are Christians by our love because we failed to give it.

Kase Johnstun is an award-winning essayist, an author, and editor whose work has appeared nationally and internationally in journals and magazines such as Creative Nonfiction Magazine, The Chronicle Review, Label Me Latina/o, Southwest Magazine, Yahoo Parenting, and many other places. Beyond the Grip of Craniosynostosis was given the Gold Quill (First Place) by the League of Utah Writers (the oldest and biggest Utah writers association) for Creative Nonfiction in 2015. He teaches for the Creative Nonfiction Foundation and for the Graduate Program in Creative Writing for SNHU.