After I dropped out of my PhD, I took the first job I was offered, because I needed it, but also because it sounded weird and interesting. It was at a small, devoutly religious Jewish school that was right in my neighbourhood, actually, though I’d never noticed it before. This was probably because it was more cleverly disguised than Hogwarts, and – it was rapidly emerging – about as impenetrable. It had no signage, and was surrounded on all sides by a series of tall, intermeshed hedges and fences.

You entered, if you could find it, through a little black door set into a wall round the back. My first day, that door was nowhere to be seen. Already late, I frantically circled the perimeter, sweating hard under the freakishly hot springtime sun. I was starting to panic when a fearsome security guard with an equally alarming orange dye job burst out of the fence at full speed. Who are you, she screamed. Who ARE you?

Her name was Shlomit, and satisfied, eventually, with the legitimacy of my presence, she unlocked the door. I followed her inside, whereupon I was immediately to discover she was something of an anomaly. With the jangling collection of marathon completion medals slung around her neck, and her lemon yellow shell suit, Shlomit was a lone tropical fish in a sea of modest, muted creatures. Men plodded the corridors in high domed velvet skullcaps and black wool coats. The women favoured ankle length skirts in sludge or navy; almost all of them wore wigs.

We climbed the stairs to the headmaster’s office. He might’ve been a pirate, with his fiery red beard, but he was not, of course: he was a rabbi. Behind him, elderly cabinets sagged with the weight of oversize volumes of Talmud. As we were introduced, he kept his eyes firmly on the carpet. Innocently, I extended my hand. Shlomit brushed it away. A lesbian rabbi called Betty Rivkah – she had two first names, because she held surnames to be oppressively patriarchal – had led the services of my childhood, with her guitar. Or sometimes, with her tambourine. This was not a world I was used to.

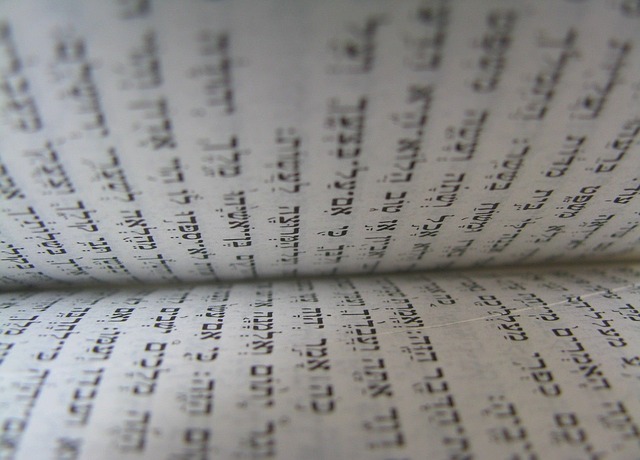

It quickly became apparent that at the school, religion was not some kind of lifestyle choice, or a hobby you did on the weekends. Instead, it was something whose ancient laws infused your every waking moment. It was to be eaten, slept, and breathed. The day was bookended by a pair of hour-long prayers, and punctuated with a series of little rituals: the kissing of the mezuzah, the washing with the double handled jug, the recitation of grace. Absolutely everyone kept strict kosher, and nobody took a bite of anything without first murmuring the appropriate blessing. Before I started, I’d thought there were three: bread, wine, and Hanukkah. There were lots more, it turned out, including one for thanking God that you’d just been to the toilet.

But of all the commandments – and there were hundreds – one in particular stood out. When you really got down to it, here was the most important thing: that religion was something to be passed on, unbent and unbroken, to the next generation. And on this point, there could be no debate. The next generation was to emerge, kicking and screaming, from a vagina that could be traced all the way back to Abraham.

The first time the question came, it was from the bosomy office secretary whom I sat down beside at lunch on my second or third day. I’d never spoken to her before, other than to ask her if she knew where the photocopier toner was, but she had a lot to say. Did I realise, for instance, that she waited six hours between consuming meat and milk, instead of the three that some people thought was fine? She also wanted to know all about me. Who were my people? I threw out a couple of tried-and-true nuggets of family lore: that my grandfather was the youngest ever captain in the Israeli navy, that my dad grew up on his ship, with a pet monkey and a parrot.

It wasn’t enough. She cocked her head, quizzically.

But is your mother Jewish?

Her little eyes tracked mine as she shoveled a forkful of bolognese into her mouth and waited for me to answer.

Now, I am lucky enough to have been blessed with a surname straight out of the back alleys of Anatevka. Glaringly Semitic. And there’s a certain kind of person who prides themselves on picking this up, invariably deciding I must be alerted to their cleverness immediately. The question of my maternal pedigree is almost guaranteed to follow, because that a complex and mystifyingly fused ethno-cultural-religious selfhood is magically inculcated into a tadpole still slurping around its mother’s amniotic fluid is the number one factoid a lot of people are very certain they know about the Jews. The first time I can remember a stranger probing me about my mum was when I was six years old. The most recent was when I was buying travel insurance.

I didn’t even need to think about it. I lied, and told the secretary, yes.

And your mother’s mother? And your mother’s mother’s mother?

I laughed at her punctiliousness, and lied again. And then, as is the nature of lies, I lied some more to other people.

Before long, I settled into the school. The weird and interesting became routine. It was a nice job: the staff were friendly and good natured, in that slightly unworldly way of the extremely devout, and the students were easy and well behaved. By the end of the first term I was humming along with morning prayers and I’d learned to lead grace. By the end of the second, I’d been invited to several weddings. I wore my skirts below the knee and my sleeves to the elbow and I slipped seamlessly in and out of the little black door like a pro.

I was there two years, in the end, and once I’d met everyone there was to meet, and survived a dozen versions of the who-are-your-family-and-where-are-they-from routine, I was relieved to find my lie didn’t surface again too often. When it did, I kept it afloat. There were a handful of awkward conversations, especially when I got engaged. Isn’t your mother upset you’re marrying out? After that, I found a four-page letter in my pigeonhole from the singing teacher, about sacred bloodlines and how I was welcome to come to ladies’ Torah study circle with her any time. And then my mum – the person I’d so casually written out of my story – put her flat up for sale, all decked out for Christmas, and the parents of a kid from my remedial reading class turned up to view it. They stood stiffly in front of the tinseled tree and talked about redoing the bathroom and where they’d put French windows, and we all pretended not to recognise each other.

*

One muggy Sunday a few months after I’d left, I was making my way home from the park when I spotted a familiar tracksuited figure jogging along the other side of the road. It was Shlomit. I watched her for a bit as she drew closer, orange ponytail bouncing up and down and neon trainers slapping the asphalt. Then she saw me and waved with both her arms, and darted perilously across the dual carriageway, grinning widely and shouting my name. We stood together on the pavement. She caught me up on the gossip, and I oohed and aahed over the engagements and the new babies and promised I would go back and see them all again very soon.

My lie was something I mostly got away with.

Holly Aszkenasy is a writer born in north London at the Royal Free Hospital, a Brutalist beauty of the highest order, and named for a pub nearby. She holds a Grade 5 award in French horn (2002), and a B in GCSE ICT for an innovative mail merge project of the same year. Holly currently resides in Manchester, where she is working on her first novel. You can find her writing here.

She read ‘But Is’ at our June 23rd live event at Gulliver’s, headlined by Amy Liptrot.